Suprematism (Russian: Супремати́зм) is an art movement, focused on basicgeometric forms, such as circles, squares, lines, and rectangles, painted in a limited range of colors. It was founded by Kazimir Malevich in Russia, around 1913, and announced in Malevich's 1915 exhibition, The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0.10, in St. Petersburg, where he, alongside 13 other artists, exhibited 36 works in a similar style.[1] The term suprematism refers to an abstract art based upon "the supremacy of pure artistic feeling" rather than on visual depiction of objects.[2]

Contents

[hide]Birth of the movement[edit]

Kazimir Malevich developed the concept of Suprematism when he was already an established painter, having exhibited in the Donkey's Tail and the Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) exhibitions of 1912 with cubo-futurist works. The proliferation of new artistic forms in painting, poetry and theatre as well as a revival of interest in the traditional folk art of Russia provided a rich environment in which a Modernist culture was born.

In "Suprematism" (Part II of his book The Non-Objective World, which was published 1927 in Munich as Bauhaus Book No. 11), Malevich clearly stated the core concept of Suprematism:

- Under Suprematism I understand the primacy of pure feeling in creative art. To the Suprematist, the visual phenomena of the objective world are, in themselves, meaningless; the significant thing is feeling, as such, quite apart from the environment in which it is called forth.

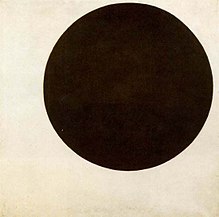

He created a suprematist "grammar" based on fundamental geometric forms; in particular, the square and the circle. In the 0.10 Exhibition in 1915, Malevich exhibited his early experiments in suprematist painting. The centerpiece of his show was the Black Square, placed in what is called the red/beautiful corner in Russian Orthodox tradition; the place of the main icon in a house. "Black Square" was painted in 1915 and was presented as a breakthrough in his career and in art in general. Malevich also paintedWhite on White which was also heralded as a milestone. "White on White" marked a shift from polychrome to monochrome Suprematism.

Distinct from Constructivism[edit]

Malevich's Suprematism is fundamentally opposed to the postrevolutionary positions ofConstructivism and materialism. Constructivism, with its cult of the object, is concerned with utilitarian strategies of adapting art to the principles of functional organization. Under Constructivism, the traditional easel painter is transformed into the artist-as-engineer in charge of organizing life in all of its aspects.

Suprematism, in sharp contrast to Constructivism, embodies a profoundly anti-materialist, anti-utilitarian philosophy. In "Suprematism" (Part II of The Non-Objective World), Malevich writes:

- Art no longer cares to serve the state and religion, it no longer wishes to illustrate the history of manners, it wants to have nothing further to do with the object, as such, and believes that it can exist, in and for itself, without "things" (that is, the "time-tested well-spring of life").

Jean-Claude Marcadé has observed that "Despite superficial similarities between Constructivism and Suprematism, the two movements are nevertheless antagonists and it is very important to distinguish between them." According to Marcadé, confusion has arisen because several artists—either directly associated with Suprematism such as El Lissitzky or working under the suprematist influence as did Rodchenko and Lyubov Popova—later abandoned Suprematism for the culture of materials.

Suprematism does not embrace a humanist philosophy which places man at the center of the universe. Rather, Suprematism envisions man—the artist—as both originator and transmitter of what for Malevich is the world's only true reality—that of absolute non-objectivity.

...a blissful sense of liberating non-objectivity drew me forth into a "desert", where nothing is real except feeling...("Suprematism", Part II of The Non-Objective World)

For Malevich, it is upon the foundations of absolute non-objectivity that the future of the universe will be built - a future in which appearances, objects, comfort, and convenience no longer dominate.

Influences on the movement[edit]

Malevich also credited the birth of suprematism to Victory Over the Sun, Kruchenykh's Futurist opera production for which he designed the sets and costumes in 1913. The aim of the artists involved was to break with the usual theater of the past and to use a "clear, pure, logical Russian language". Malevich put this to practice by creating costumes from simple materials and thereby took advantage of geometric shapes. Flashing headlights illuminated the figures in such a way that alternating hands, legs or heads disappeared into the darkness. The stage curtain was a black square. One of the drawings for the backcloth shows a black square divided diagonally into a black and a white triangle. Because of the simplicity of these basic forms they were able to signify a new beginning.

Another important influence on Malevich were the ideas of the Russian mystic, philosopher, and disciple of Georges Gurdjieff, P. D. Ouspensky, who wrote of "a fourth dimension or a Fourth Way beyond the three to which our ordinary senses have access".[4]

Some of the titles to paintings in 1915 express the concept of a non-Euclidean geometrywhich imagined forms in movement, or through time; titles such as: Two dimensional painted masses in the state of movement. These give some indications towards an understanding of the Suprematic compositions produced between 1915 and 1918.

The Supremus journal[edit]

The Supremus group, which in addition to Malevich included Aleksandra Ekster, Olga Rozanova, Nadezhda Udaltsova, Ivan Kliun, Lyubov Popova, Lazar Khidekel, Nikolai Suetin, Ilya Chashnik, Nina Genke-Meller, Ivan Puni and Ksenia Boguslavskaya, met from 1915 onwards to discuss the philosophy of Suprematism and its development into other areas of intellectual life. The products of these discussions were to be documented in a monthly publication called Supremus, titled to reflect the art movement it championed, that would include painting, music, decorative art, and literature. Malevich conceived of the journal as the contextual foundation in which he could base his art, and originally planned to call the journal Nul. In a letter to a colleague, he explained:

- We are planning to put out a journal and have begun to discuss the how and what of it. Since in it we intend to reduce verything to zero, we have decided to call it Nul. Afterward we ourselves will go beyond zero.

Malevich conceived of the journal as a space for experimentation that would test his theory of nonobjective art. The group of artists wrote several articles for the initial publication, including the essays "The Mouth of the Earth and the Artist" (Malevich), "On the Old and the New in Music" (Matiushin), "Cubism, Futurism, Suprematism" (Rozanova), "Architecture as a Slap in the Face to Ferroconcrete" (Malevich), and "The Declaration of the Word as Such" (Kruchenykh). However, despite a year spent planning and writing articles for the journal, the first issue of Supremus was never published.[5]

El Lissitzky: a bridge to the west[edit]

The most important artist who took the art form and ideas developed by Malevich and popularized them abroad was the painter El Lissitzky. Lissitzky worked intensively with Suprematism particularly in the years 1919 to 1923. He was deeply impressed by Malevich's Suprematist works as he saw it as the theoretical and visual equivalent of the social upheavals taking place in Russia at the time. Suprematism, with its radicalism, was to him the creative equivalent of an entirely new form of society. Lissitzky transferred Malevich’s approach to hisProun constructions, which he himself described as "the station where one changes from painting to architecture". The Proun designs, however, were also an artistic break from Suprematism; the "Black Square" by Malevich was the end point of a rigorous thought process that required new structural design work to follow. Lissitzky saw this new beginning in his Proun constructions, where the term "Proun" (Pro Unovis) symbolized its Suprematist origins.

Lissitzky exhibited in Berlin in 1923 at the Hanover and Dresden showrooms of Non-Objective Art. During this trip to the West, El Lissitzky was in close contact with Theo van Doesburg, forming a bridge between Suprematism and De Stijl and the Bauhaus.

Architecture[edit]

Lazar Khidekel (1904-1986), Suprematist artist and visionary architect, was the only Suprematist architect who emerged from the Malevich circle. Khidekel started his study in architecture in Vitebsk art school under El Lissitzky in 1919-20. He was instrumental in the transition from planar Suprematism to volumetric Suprematism, creating axonometric projections (The Aero-club: Horizontal architecton, 1922–23), making three-dimensional models, such as the architectons, designing objects (model of an "Ashtray", 1922–23), and producing the first Suprematist architectural project (The Workers’ Club, 1926). In the mid-1920s, he began his journey into the realm of visionary architecture. Directly inspired by Suprematism and its notion of an organic form-creation continuum, he explored new philosophical, scientific and technological futuristic approaches, and proposed innovative solutions for the creation of new urban environments, where people would live in harmony with nature and would be protected from man-made and natural disasters (his still topical proposal for flood protection - the City on the Water, 1925, etc.).

Nikolai Suetin used Suprematist motifs on works at the St. Petersburg Lomonosov Porcelain Factory where Malevich and Chashnik were also employed, and Malevich designed a Suprematist teapot. The Suprematists also made architectural models in the 1920s which offered a different conception of socialist buildings to those developed in Constructivist architecture.

Malevich's architectural projects were known after 1922 Arkhitektoniki. Designs emphasized the right angle, with similarities to De Stijl and Le Corbusier, and were justified with an ideological connection to communist governance and equality for all. Another part of the formalism was low regard for triangles which were "dismissed as ancient, pagan, orChristian".[6]

The first Suprematist Architectural project was created by Lazar Khidekel in 1926. In the mid 1920s to 1932 Lazar Khidekel also created a series of futuristic projects such as Aero-City, Garden-City, and City Over Water.

Social context[edit]

This development in artistic expression came about when Russia was in a revolutionary state, ideas were in ferment, and the old order was being swept away. As the new order became established, and Stalinism took hold from 1924 on, the state began limiting the freedom of artists. From the late 1920s the Russian avant-garde experienced direct and harsh criticism from the authorities and in 1934 the doctrine of Socialist Realism became official policy, and prohibited abstraction and divergence of artistic expression. Malevich nevertheless retained his main conception. In his self-portrait of 1933 he represented himself in a traditional way—the only way permitted by Stalinist cultural policy—but signed the picture with a tiny black-over-white square.

Notable exhibitions[edit]

Historic Exhibitions

- Exhibition of Modern Decorative Art at Lemercier Gallery, Moscow, 1915

- The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0.10 at Galerie Dobychina, Petrograd, 1915

- First Russian Art Exhibition at Galerie Van Diemen, Berlin, 1922

- First State Exhibition of Local and Moscow Artists, Vitebsk, 1919

- Exhibition of Paintings by Petrograd Artists of All Trends, 1918-1923, Petrograd, 1923

Retrospective Exhibitions

- The Great Utopia: The Russian and Soviet Avant-Garde, 1915-1932 at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 1992

- Malevich’s Circle. Confederates. Students. Followers in Russia 1920s-1950s at The State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, 2000

- Kazimir Malevich: Suprematism at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2003

- Zaha Hadid and Suprematism at Galerie Gmurzynska, Zürich, 2010

- Lazar Khidekel: Surviving Suprematism" at Judah L. Magnes Museum, Berkeley CA, 2004-2005

- Lazar Markovich Khidekel – the Rediscovered Suprematist at House Konstruktiv, Zurich, 2010-2011

- Kazimir Malevich and the Russian Avant-Garde at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 2013

- Malevich: Revolutionary of Russian Art at the Tate Modern, London, 2014

- Floating Worlds and Future Cities. Genius of Lazar Khidekel, Suprematism and Russian Avant-garde. NYC, 2013

Artists associated with Suprematism[edit]

References and sources[edit]

- References

- ^ Honour, H. and Fleming, J. (2009) A World History of Art. 7th edn. London: Laurence King Publishing, pp. 793–795. ISBN 9781856695848

- ^ Malevich, Kazimir (1927). The Non-Objective World. Munich.

- ^ MOMA, The Collection, accessed January 4, 2013

- ^ (Gooding, 2001)

- ^ Drutt, Matthew (2003). Kazimir Malevich: Suprematism. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications. pp. 44–60. ISBN 0-89207-265-2.

- ^ Hanno-Walter Kruft, Elsie Callander, Ronald Taylor, and Antony Wood A history of architectural theory: from Vitruvius to the present Edition 4 Publisher Princeton Architectural Press, 2003 ISBN 978-1-56898-010-2, p. 416

- Sources

- Kasimir Malevich, The Non-Objective World. English translation by Howard Dearstyne from the German translation of 1927 by A. von Riesen from Malevich's original Russian manuscript, Paul Theobald and Company, Chicago, 1959.

- Camilla Gray, The Russian Experiment in Art, Thames and Hudson, 1976.

- Mel Gooding, Abstract Art, Tate Publishing, 2001.

- Jean-Claude Marcadé, "What is Suprematism?", from the exhibition catalogue, Kasimir Malewitsch zum 100. Geburtstag, Galerie Gmurzynska, Cologne, 1978.

Further reading[edit]

- Jean-Claude Marcadé, "Malevich, Painting and Writing: On the Development of a Suprematist Philosophy", Kazimir Malevich: Suprematism, Guggenheim Museum, April 17, 2012 [Kindle Edition]

- Jean-Claude Marcadé, "Some Remarks on Suprematism"; and Emmanuel Martineau, "A Philosophy of the 'Suprema' ", from the exhibition catalogue Suprematisme, Galerie Jean Chauvelin, Paris, 1977

- Miroslav Lamac and Juri Padrta, "The Idea of Suprematism", from the exhibition catalogue, Kasimir Malewitsch zum 100. Geburtstag, Galerie Gmurzynska, Cologne, 1978

- Lazar Khidekel and Suprematism. Regina Khidekel, Charlotte Douglas, Magdolena Dabrowsky, Alla Rosenfeld, Tatiand Goriatcheva, Constantin Boym. Prestel Publishing, 2014.

- S. O. Khan-Magomedov. Lazar Khidekel (Creators of Russian Classical Avant-garde series), M., 2008

- Alla Efimova . Surviving Suprematism: Lazar Khidekel. Judah L. Magnes Museum, Berkeley CA, 2004.

- S.O. Khan-Magomedov. Pioneers of the Soviet Design. Galart, Moscow, 1995.

- Selim Khan-Magomedov, Regina Khidekel. Lazar Markovich Khidekel. Suprematism and Architecture. Leonard Hutton Galleries, New York, 1995.

- Alexandra Schatskikh. Unovis: Epicenter of a New World. The Great Utopia.The Russian and Soviet Avant-Garde 1915-1932.- Solomon Guggenheim Museum, 1992, State Tretiakov Gallery, State Russian Museum, Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt.

- Mark Khidekel. Suprematism and Architectural Projects of Lazar Khidekel. Architectural Design 59, # 7-8, 1989

- Mark Khidekel. Suprematism in Architecture. L’Arca, Italy, # 27, 1989

- Selim O. Chan-Magomedow. Pioniere der sowjetischen Architectur, VEB Verlag der Kunst, Dresden, 1983.

- Larissa A. Zhadova.Malevich: Suprematism and Revolution in Russian Art 1910-1030, Thames and Hudson, London, 1982.

- Larissa A. Zhadowa. Suche und Experiment. Russische und sowjetische Kunst 1910 bis 1930, VEB Verlag der Kunst, Dresden, 1978

- Suprematism is a highly geometric style of 20th-century abstract painting, developed by Russian artist Kazimir Malevich. The term suprematism refers to an art based upon the supremacy of "pure artistic feeling" rather than on the depiction of objects. In 1913 Malevich executed his first suprematist composition: a pencil drawing of a black square on a white background. In 1915 he published a manifesto and for the first time displayed his suprematist compositions at an exhibition.Malevich's earliest suprematist works were among his most severe, consisting of basic geometric shapes, such as circles, squares, and rectangles, painted in a limited range of colors. In the following years he gradually introduced more colors as well as triangles and fragments of circles. He also began to restore some illusion of depth to his compositions. Having attained this ultimate point of abstraction, Malevich declared in 1919 that the suprematist experiment had finished.Any attempt to interpret suprematism inevitably draws upon Malevich's own explanation of the movement. Malevich distinguished his work not only from depictions of external reality, but also from any art that attempted to represent the emotions of its creator. He intended suprematism, by contrast, to express "the metallic culture of our time," and he occasionally made direct references to technology in his art.In general, Malevich used perfect abstract shapes such as the square as symbols of humanity's ability to transcend the natural world. Malevich was extremely interested in the mystical movement theosophy and in expressing a spiritual reality beyond the physical through his art. In this context the black square of his first suprematist work was not empty, as his critics claimed. Instead it was "filled with the spirit of non-objective sensation," according to the artist, who described the areas of white in his compositions as "the free white sea" of "infinity." This liberation from finite earthly existence reached a fitting climax in his white-on-white paintings, where the square finally lost its physical presence and merged with its brilliant white background.

Suprematism Manifesto

Under Suprematism I understand the supremacy of pure feeling in creative art. To the Suprematist the visual phenomena of the objective world are, in themselves, meaningless; the significant thing is feeling, as such, quite apart from the environment in which it is called forth.The so called "materialization" of a feeling in the conscious mind really means a materialization of the reflection of that feeling through the medium of some realistic conception. Such a realistic conception is without value in Suprematist art... And not only in Suprematist art but in art generally, because the enduring, true value of a work of art (to whatever school it may belong) resides solely in the feeling expressed.Academic naturalism, the naturalism of the Impressionists, Cezanneism, Cubism, etc all these, in a way, are nothing more than dialectic methods which, as such, in no sense determine the true value of an art work.An objective representation, having objectivity as its aim, is something which, as such, has nothing to do with art, and yet the use of objective forms in an art work does not preclude the possibility of its being of high artistic value.Hence, to the Suprematist, the appropriate means of representation is always the one which gives fullest possible expression to feeling as such and which ignores the familiar appearance of objects.Objectivity, in itself, is meaningless to him; the concepts of the conscious mind are worthless.Feeling is the determining factor... and thus art arrives at non objective representation at Suprematism.It reaches a "desert" in which nothing can be perceived but feeling.Everything which determined the objective ideal structure of life and of "art' ideas, concepts, and images all this the artist has cast aside in order to heed pure feeling.The art of the past which stood, at least ostensibly, in the service of religion and the state, will take on new life in the pure (unapplied) art of Suprematism, which will build up a new world the world of feeling...When, in the year 1913, in my desperate attempt to free art from the ballast of objectivity, I took refuge in the square form and exhibited a picture which consisted of nothing more than a black square on a white field, the critics and, along with them, the public sighed, "Everything which we loved is lost. We are in a desert... Before us is nothing but a black square on a white background!"

"Withering" words were sought to drive off the symbol of the "desert" so that one might behold on the "dead square" the beloved likeness of "reality" ("true objectivity" and a spiritual feeling).The square seemed incomprehensible and dangerous to the critics and the public... and this, of course, was to be expected.The ascent to the heights of nonobjective art is arduous and painful... but it is nevertheless rewarding. The familiar recedes ever further and further into the background... The contours of the objective world fade more and more and so it goes, step by step, until finally the world "everything we loved and by which we have lived" becomes lost to sight.No more "likenesses of reality," no idealistic images nothing but a desert!But this desert is filled with the spirit of nonobjective sensation which pervades everything.Even I was gripped by a kind of timidity bordering on fear when it came to leaving "the world of will and idea," in which I had lived and worked and in the reality of which I had believed.But a blissful sense of liberating nonobjectivity drew me forth into the "desert," where nothing is real except feeling... and so feeling became the substance of my life.This was no "empty square" which I had exhibited but rather the feeling of nonobjectivity.I realized that the "thing" and the "concept" were substituted for feeling and understood the falsity of the world of will and idea.Is a milk bottle, then, the symbol of milk?Suprematism is the rediscovery of pure art which, in the course of time, had become obscured by the accumulation of "things."It appears to me that, for the critics and the public, the painting of Raphael, Rubens, Rembrandt, etc., has become nothing more than a conglomeration of countless "things," which conceal its true value the feeling which gave rise to it. The virtuosity of the objective representation is the only thing admired.

If it were possible to extract from the works of the great masters the feeling expressed in them the actual artistic value, that is and to hide this away, the public, along with the critics and the art scholars, would never even miss it.So it is not at all strange that my square seemed empty to the public.If one insists on judging an art work on the basis of the virtuosity of the objective representation the verisimilitude of the illusion and thinks he sees in the objective representation itself a symbol of the inducing emotion, he will never partake of the gladdening content of a work of art.The general public is still convinced today that art is bound to perish if it gives up the imitation of "dearly loved reality" and so it observes with dismay how the hated element of pure feeling abstraction makes more and more headway...Art no longer cares to serve the state and religion, it no longer wishes to illustrate the history of manners, it wants to have nothing further to do with the object, as such, and believes that it can exist, in and for itself, without "things" (that is, the "time tested well spring of life").But the nature and meaning of artistic creation continue to be misunderstood, as does the nature of creative work in general, because feeling, after all, is always and everywhere the one and only source of every creation.The emotions which are kindled in the human being are stronger than the human being himself... they must at all costs find an outlet they must take on overt form they must be communicated or put to work.It was nothing other than a yearning for speed... for flight... which, seeking an outward shape, brought about the birth of the airplane. For the airplane was not contrived in order to carry business letters from Berlin to Moscow, but rather in obedience to the irresistible drive of this yearning for speed to take on external form.The "hungry stomach" and the intellect which serves this must always have the last word, of course, when it comes to determining the origin and purpose of existing values... but that is a subject in itself.And the state of affairs is exactly the same in art as in creative technology... In painting (I mean here, naturally, the accepted "artistic" painting) one can discover behind a technically correct portrait of Mr. Miller or an ingenious representation of the flower girl at Potsdamer Platz not a trace of the true essence of art no evidence whatever of feeling. Painting is the dictatorship of a method of representation, the purpose of which is to depict Mr. Miller, his environment, and his ideas.

The black square on the white field was the first form in which nonobjective feeling came to be expressed. The square = feeling, the white field = the void beyond this feeling.Yet the general public saw in the nonobjectivity of the representation the demise of art and failed to grasp the evident fact that feeling had here assumed external form.The Suprematist square and the forms proceeding out of it can be likened to the primitive marks (symbols) of aboriginal man which represented, in their combinations, not ornament but a feeling of rhythm.Suprematism did not bring into being a new world of feeling but, rather, an altogether new and direct form of representation of the world of feeling.The square changes and creates new forms, the elements of which can be classified in one way or another depending upon the feeling which gave rise to them.When we examine an antique column, we are no longer interested in the fitness of its construction to perform its technical task in the building but recognize in it the material expression of a pure feeling. We no longer see in it a structural necessity but view it as a work of art in its own right."Practical life," like a homeless vagabond, forces its way into every artistic form and believes itself to be the genesis and reason for existence of this form. But the vagabond doesn't tarry long in one place and once he is gone (when to make an art work serve "practical purposes" no longer seems practical) the work recovers its full value.Antique works of art are kept in museums and carefully guarded, not to preserve them for practical use but in order that their eternal artistry may be enjoyed.The difference between the new, nonobjective ("useless") art and the art of the past lies in the fact that the full artistic value of the latter comes to light (becomes recognized) only after life, in search of some new expedient, has forsaken it, whereas the unapplied artistic element of the new art outstrips life and shuts the door on "practical utility."And so there the new nonobjective art stands the expression of pure feeling, seeking no practical values, no ideas, no promised land...The Suprematists have deliberately given up objective representation of their surroundings in order to reach the summit of the true "unmasked" art and from this vantage point to view life through the prism of pure artistic feeling.Nothing in the objective world is as "secure and unshakeable" as it appears to our conscious minds. We should accept nothing as predetermined as constituted for eternity. Every "firmly established," familiar thing can be shifted about and brought under a new and, primarily, unfamiliar order. Why then should it not be possible to bring about an artistic order?...Our life is a theater piece, in which nonobjective feeling is portrayed by objective imagery.A bishop is nothing but an actor who seeks with words and gestures, on an appropriately "dressed" stage, to convey a religious feeling, or rather the reflection of a feeling in religious form. The office clerk, the blacksmith, the soldier, the accountant, the general... these are all characters out of one stage play or another, portrayed by various people, who become so carried away that they confuse the play and their parts in it with life itself We almost never get to see the actual human face and if we ask someone who he is, he answers, "an engineer," "a farmer," etc., or, in other words, he gives the title of the role played by him in one or another effective drama.The title of the role is also set down next to his full name, and certified in his passport, thus removing any doubt concerning the surprising fact that the owner of the passport is the engineer Ivan and not the painter Kasimir.In the last analysis, what each individual knows about himself is precious little, because the "actual human face" cannot be discerned behind the mask, which is mistaken for the "actual face."The philosophy of Suprematism has every reason to view both the mask and the "actual face" with skepticism, since it disputes the reality of human faces (human forms) altogether.Artists have always been partial to the use of the human face in their representations, for they have seen in it (the versatile, mobile, expressive mimic) the best vehicle with which to convey their feelings. The Suprematists have nevertheless abandoned the representation of the human face (and of natural objects in general) and have found new symbols with which to render direct feelings (rather than externalized reflections of feelings), for the Suprematist does not observe and does not touch - he feels.

We have seen how art, at the turn of the century, divested itself of the ballast of religious and political ideas which had been imposed upon it and came into its own attained, that is, the form suited to its intrinsic nature and became, along with the two already mentioned, a third independent and equally valid point of view." The public is still, indeed, as much convinced as ever that the artist creates superfluous, impractical things. it never considers that these superfluous things endure and retain their vitality for thousands of years, whereas necessary, practical things survive only briefly.It does not dawn on the public that it fails to recognize the real, true value of things. This is also the reason for the chronic failure of everything utilitarian. A true, absolute order in human society could only be achieved if mankind were willing to base this order on lasting values. Obviously, then, the artistic factor would have to be accepted in every respect as the decisive one. As long as this is not the case, the uncertainty of a "provisional order" will obtain, instead of the longed for tranquillity of an absolute order, because the provisional order is gauged by current utilitarian understanding and this measuring stick is variable in the highest degree.In the light of this, all art works which, at present, are a part of "practical life" or to which practical life has laid claim, are in some senses devaluated. Only when they are freed from the encumbrance of practical utility (that is, when they are placed in museums) will their truly artistic, absolute value be recognized.The sensations of sitting, standing, or running are, first and foremost, plastic sensations and they are responsible for the development of corresponding 61 objects of use and largely determine their form.A chair, bed, and table are not matters of utility but rather, the forms taken by plastic sensations, so the generally held view that all objects of daily use result from practical considerations is based upon false premises.We have ample opportunity to become convinced that we are never in a position for recognizing any real utility in things and that we shall never succeed in constructing a really practical object. We can evidently only feel the essence of absolute utility but, since a feeling is always nonobjective, any attempt to grasp the utility of the objective is Utopian. The endeavor to confine feeling within concepts of the conscious mind or, indeed, to replace it with conscious concepts and to give it concrete, utilitarian form, has resulted in the development of all those useless, "practical things" which become ridiculous in no time at all.It cannot be stressed to often that absolute, true values arise only from artistic, subconscious, or superconscious creation.The new art of Suprematism, which has produced new forms and form relationships by giving external expression to pictorial feeling, will become a new architecture: it will transfer these forms from the surface of canvas to space.

The Suprematist element, whether in painting or in architecture, is free of every tendency which is social or other wise materialistic.Every social ideal however great and important it may be, stems from the sensation of hunger; every art work, regardless of how small and insignificant it may seem, originates in pictorial or plastic feeling. It is high time for us to realize that the problems of art lie far apart from those of the stomach or the intellect.Now that art, thanks to Suprematism, has come into its own that is, attained its pure, unapplied form and has recognized the infallibility of nonobjective feeling, it is attempting to set up a genuine world order, a new philosophy of life. It recognizes the nonobjectivity of the world and is no longer concerned with providing illustrations of the history of manners.Nonobjective feeling has, in fact, always been the only possible source of art, so that in this respect Suprematism is contributing nothing new but nevertheless the art of the past, because of its use of objective subject matter, harbored unintentionally a whole series of feelings which were alien to it.But a tree remains a tree even when an owl builds a nest in a hollow of it.Suprematism has opened up new possibilities to creative art, since by virtue of the abandonment of so called "practical consideration," a plastic feeling rendered on canvas can be carried over into space. The artist (the painter) is no longer bound to the canvas (the picture plane) and can transfer his compositions from canvas to space.© 1926 Kazimir Malevich.

Нема коментара:

Постави коментар